SURVEY

Migrant Sex Workers and the Covid-19 crisis

The European TAMPEP network members conducted a survey on the situation of female, male and transgender migrant sex workers and their access to basic health services since the pandemic start.

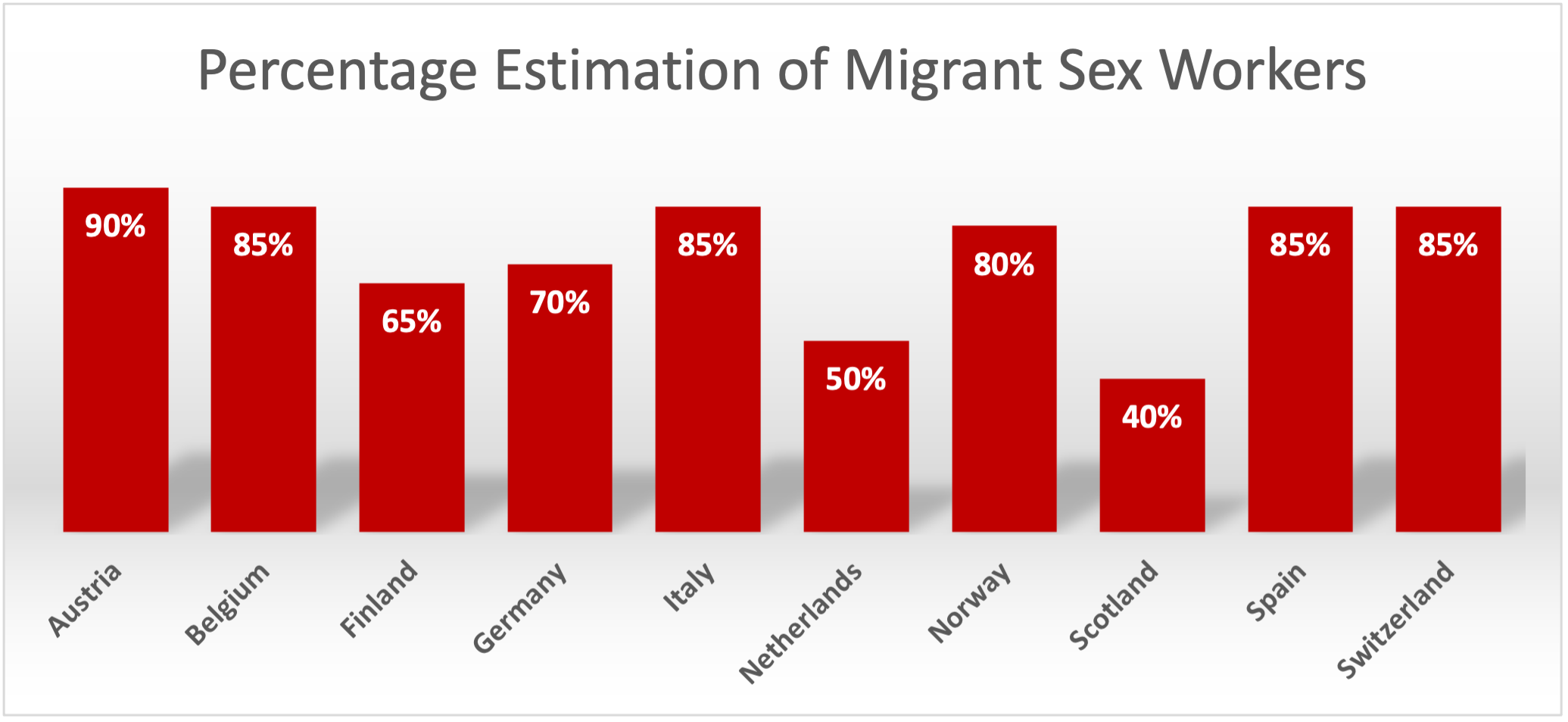

The survey was carried out in March 2021 by 14 TAMPEP Network organisations in 10 European countries – Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Scotland (UK), Spain and Switzerland – all expert services targeting migrant sex workers.

The present document is a summary of the survey, with its most relevant issues. The same regarding the qualitative data analysis. The evidences shown are the basis of the TAMPEP Declaration and Petition[1] in the framework of the TAMPEP campaign Migrant Sex Workers call for Rights.

The aim of the survey was to understand how the negative consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic disproportionately affected those already vulnerable and those on the fringes of society.

Migrant sex workers across Europe have witnessed increasing levels of poverty and exclusion, not only socially but also from services and support, accessible to other groups in society.

Despite the fact that since June/July 2021 the more restrictive measures against Covid-19 has been revised across Europe, organizations and sex workers across the continent are still reporting about the degradation of the situation, including the exclusion of migrant workers from national and European support that has been made available to other groups.

Many migrant sex workers were already vulnerable regarding unstable housing conditions, debt and isolation. The ongoing crisis have seen the issues been exacerbated considerably. In countries where sex work is criminalized, where sex workers operate covertly, the risk of violence from clients and law enforcement has risen significantly because of the crisis.

Qualitative Data Analysis

One obvious fact caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, is the theme of socio-economic disadvantage, which is directly linked to that of marginality. Pockets of exclusion that were already widely present have expanded as the inequality gap and the pool of vulnerable individuals has widened. The spread of the virus has had a major impact on the socio-economic system, making critical points and systematic distortions that affects sex work and the impact of social exclusion more evident.

The issue of labour, physical and mental health, as well as social security has become more prominent. This lead to critical situations like poverty and Human Rights violations, experienced also by migrant sex workers. Poverty has always been identified as one of the factors that makes people more vulnerable, which includes trafficking and other forms of exploitation.

We are seeing migrant and mobile sex workers’ communities in conditions of extreme poverty as a result of the loss of income in sex work and in other forms of informal labour. For sex workers, who many times work in both, and their families, who mostly work in the informal sector, that impact was particularly severe. Migrant sex workers and their families, who do not benefit from welfare support, are at high risk of exploitation due to the prolonged absence of income, affecting an entire community of reference and support.

Particularly worrying are the conditions of dependency linked to debts, incurred in order to survive, and situations where debt obligations raised the levels of violence, blackmail and subjugation.

Another consequence is the loss of housing, already precarious for many migrants sex workers, either because they lived in the workplace or because they were unable to afford the high rent costs.

It is a fact that in a mechanism of community subsistence and families’ support, a desperate economic condition affects the whole community and not only the individual.

Measures taken to contain the development of the infection curve have involved forced quarantine, major restrictions on people’s movements and limitations on economic activities. People’s public and private lives were disrupted through the conversion of all possible social relationships into virtual forms, like home office. All this has occurred in a very short period of time, which contributed to an acceleration of a process of increased vulnerability.

During the pandemic, vulnerable populations are disproportionately affected, and pre-existing vulnerabilities exacerbated. The policies and measures adopted during the pandemic are decisive in measuring the capacity of governments to implement social protection and inclusive policies that respond to the needs of the most vulnerable and at the same time an effective Covid-19 response.

Considering democratic standars it is a crucial political choice whether or not it respects the fundamental rights of the residents in its territory, regardless of the legal or labour status of the persons.

Lack of support for migrants

Sex workers’-led organisations and community base organisations has been confronted with lack of information for migrants, a total lack of state interventions addressed to migrants and migrant women, including socially isolated communities like undocumented sex workers.

At the same time, the dissemination of Covid-19 has led to a rethinking, even if only as an emergency act, in the way certain services are offered to sex workers. However, it has been sex workers’ organisations themselves that has been taken the forefront in this emergency period. There was an immediate need to strengthen initiatives aimed to provide the communities with their necessary basic needs, to give continuity to the support services already operating in the field, to mobilise activities of practical support, to advocate for the protection of sex workers’ rights, to denounce discrimination and demand for political attention to this group.

The pandemic highlighted social inequalities

It became evident early on in the pandemic that the root causes of social inequalities would be exacerbated, widening the possibility that many migrants, among others, would find themselves increasingly exposed to severe exploitation, simply because they were unable to move. For thousands of people, the worry of being able to pay their bills end of the month and to send something home has turned into anxiety about being able to eat at the end of each day.

Increased border controls due to Covid-19 and restrictive travel measures reduced the freedom of movement of mobile sex workers, like those who work periodically in one country and return to their country of origin, locking them in a country where they had neither labour resources nor residence.

The illegalization of sex work and the prolonged lockdowns has reduced considerably the negotiation power of sex workers, who have often been forced to accept very bad working conditions, including the reduction of prices of services offered. It also exposed them to the risks of abusive of both clients and managers.

Exclusion from social and health services

Precarious living conditions and insecurity regarding residence or work status have also led to sex workers’ increased exposure to Covid-19, adding health vulnerability to the already mentioned social and economic vulnerabilities.

In some European countries, the closure of low-threshold services due to the lockdown meant an exclusion from essential health or social support services. The lack of services also meant no ‘cultural mediation’ or interpretation that allows many migrant sex workers the access to information. The lack of access to multilingual information about norms and sanctions, and the closure of workplace has excluded a large number of them from reliable information and therefore, of making decisions.

Furthermore, the fear of being identified as either undocumented or partially documented, for being punished for exercising sex work or doing it in premises considered non-legal, has created a visible distance from primary health care services, even in countries where the access to a public health system was possible.

Paradoxical situations were also reported in countries with mandatory health monitoring systems, like in Austria. The fact that the services were closed made it illegal to work even when prostitution premises were open, because of the absence of health checks certification.

At the same time, we have received reports that the practices of deportation and imprisonment in deportation centres have continued even during the current crisis, despite the demands of migrant rights organisations and networks for a moratorium.

The risks for those who were forced by necessity to work on the streets in situations of visibility have increased with double administrative fines for violating curfew or lockdown measures and administrative sanctions due to ordinances against street prostitution.

Fines has increased the economic difficulties that forced people to go out and work, despite the bans, bringing precariousness and indigence even further in a situation that is already of great vulnerability. Many of the emergency funds created by sex workers’ organizations have been dedicated to packages of basic foodstuffs, where the situation of sex workers is far below the poverty level.

Migrants sex workers have been disproportionately affected by both the direct effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictive migration measures put in place, which, in turn, have hampered coordinated and consistent public health responses.

An integrated approach to migration, sex work and public health policies covering social protection measures, a flexible approach to migration status and non-discriminatory access to health care is essential to uphold international conventions protecting the right to health without discrimination.

CONCLUSIONS

The pandemic has highlighted, as never before, the inherent hostility and discrimination of normative and administrative models towards migrant sex workers, due to a double criminalization: as sex workers and as migrants.

Regardless of the prostitution system in the different countries, punitive practices have reached individuals severely, criminalising sex workers already in a quite precarious situation due to the pandemic. The double criminalisation shows a strong tendency of a type of normative violence against vulnerable people, instead of supporting and ensuring them the protection of their human rights.

Moreover, the debate on a sex purchase ban has gained momentum again during the pandemic, thus shifting the focus to the lack of support and impact of the crisis on the most vulnerable, to increased the stigmatisation of sex work and migrant labour.

In this repressive context, it seems that legislators and institutions are using the excuse of Covid-19 health measures, to fight against prostitution and not to protect workers and their health.

This system of multiple forms of discrimination and institutionalised punitive systems has increased the risk of migrant sex workers being victims of criminal violence and robbery. The more vulnerable one is the more one is at risk.

We are talking about a population that is mostly excluded from all forms of social benefits and emergency measures put in place by the State during the Covid-19 pandemic. Citizens that are not considered as having rights, made invisible, lead to social exclusion, abuse of their rights, up to a generalised situation of extreme social and economic vulnerability.

An unworthy situation for any democratic society.

RECCOMANDATIONS

Migrant communities, regardless of status, have the right to life, liberty, and security. They have the right to be free from discrimination and to have an adequate standard of living. This basic rights have not been protected and secured in the current crisis.

Measures to protect those made particularly vulnerable, such as migrant sex workers, must urgently be considered. Human rights must form the backbone of any integrated approach to public health, sex work and migration policies.

1. Guarantee barrier-free access to healthcare services for all, including migrant sex workers and other potentially criminalised communities in accordance with UNAIDS, UNHCR, IOM and WHO recommendations.

2. Guarantee access to full vaccination for undocumented migrants, with no administrative and/or immigration requirements. Produce free multilingual information accessible before and while vaccinating migrant communities.

3. Guarantee access to public services without penalisation or risk of deportation.

4. Guarantee access to funding for community based services and organisations advocating for migrant sex workers’ rights.

5. Stop using pandemic regulations to unfairly arrest, detain, heavily fine and deport migrant sex workers.

6. Ensure no person is held in breach of visa conditions for overstaying due to reasons related to COVID-19 and released, though held in detention under immigration powers to reduce risk of COVID-19 outbreaks and humanitarian catastrophe.

7. Enforce migration policies that are inclusive and respectful of the Human Rights of migrant Sex Workers while guaranteeing their legal protection.

The situation for migrant sex workers due to covid-19

AUSTRIA

n Austria, sex work is regulated and health examinations are mandatory at local medical services. Between July and October 2020, it was possible to work in sex work without too many restrictions, otherwise it was forbidden. Most sex workers/SW did not get financial support because the State asked for specific criteria, which many migrants could not fulfil, causing greater isolation, different sorts of dependencies and the danger of getting homeless.

Every region can interpret regulations differently. Some medical services were closed, and SW got fines for not having done the exams, yet they were not being offered… Many SW could not work legally because brothels were closed, house calls forbidden and no jobs in other areas available. Many SW did not get the information they needed because they did not know German: most public services could only be accessed online or over the phone. To know if SW worked and lived in the same place, police officers, disguised as clients, used the portal where SW advertise to carry out investigations.

Since June 2021, it is possible to work again, but it is not financially secure as sex work was driven into illegality during lockdowns. Sex work, quite often takes place under precarious working conditions. During lockdown, the debate on a sex purchase ban has gained notoriety again and the stigma against SW has reached registered as well as unregistered sex workers.

BELGIUM

In Belgium, sex work is regulated. Sex workers were not allowed to work officially because it was forbidden to do sex work during the lockdown. Migrant SW, documented or not, worked in a clandestine manner, as did those with a regulated status and Belgian sex workers.

This underground, illegal working and living conditions lead to health, violence and social risks.

Sex workers with no income were having problems even to buy food, which lead them to extreme survival strategies. They were extremely isolated, also due to travel restrictions, and without any prospect of improving their situation. The consequences were additional psychological problems.

Since June, restrictive measures such as the closure of prostitution premises have been lifted and travel is possible, but socio-economic conditions remain extremely precarious, particularly due to debts and the definitive closure of many premises. Moreover, special measures are still in place for sex work premises, which have an impact in the volume of clients and incomes.

FINLAND

In Finland, sex work follows a prohibitionist model. The situation was and is extremely difficult. Many migrant SW have no income, what increased their need of lending money, leading to debt bondage and no perspective on how to pay it back. The context increased the risk of abuse and violence, as well as isolation, mental problems and substance abuse. Migrant SW have no or only limited access to health services, and an enormous lack of information.

GERMANY

In Germany, sex work is legalized and regulated. Since 2017, with the new Law on Prostitution, SW have to register and attend mandatory health counselling. The situation of sex workers, including migrants, depends if they are registered or not. Migrants can only be registered if they have a legal status. There are about 40.000 SW registered, from an estimation of about 200.000 SW.

If registered and able to provide information on their Tax Declaration of 2019 (since March 2020 they were forbidden to work), they had the right to get State financial support during the pandemic period.

The majority, non-registered, did not get any sort of State support. For migrant sex workers the situation became critical, with no work possibilities as brothels, flats, clubs, etc. had to close. Sex workers’ organisations were and still are the only ones to support this group financially.

Illegality has been leading to dependency, exploitation, services offered at lower prices and more violence. Illegality hindered migrant sex workers to look for support or advice at NGOs and public health services for fear of being denounced as illegal sex workers. Stigmatisation has led to accuse sex workers of being ‘super-spreaders of covid-19’. Discrimination against migrants has increased.

Sex work is allowed again since June 2021. The consequences of Covid-19, however, are catastrophic, mainly for migrant sex workers. Many work places, like small brothels and private apartments were forced to close during the pandemic and did not open again. Mobility increased and the working conditions worsened considerably since the reopening, because of less work places.

ITALY

In Italy, individual sex work is legal but not regulated. All other forms are forbidden. SW’s situation is very precarious. The mobility restrictions reduced the possibility of meeting customers on the street and indoors. Since March 2020, the lockdown has incresed poverty and debts among SW. As most are migrants and highly mobile, SW find themselves without a family network or any governmental support.

The problems during lockdown were the lack of food and hygiene products, disinfectants and masks. Some SW did not have a home and lived in residences that were also workplaces, with very high costs, which they could not pay. Migrant SW were supported by social organizations, a crowdfunding organized by a collective of SW, organizations for migrants’, LGBTQI’ rights and private donations.

In this desperate situation, some SW choose to work on the street, despite prohibitions, curfews and lockdowns. The reactions of the police were always very punitive, with high fines and violent reprisals. Those who managed to organize themselves worked indoors, but customers have decreased.

The transgender population had greater difficulty in leaving the street at this time. Among those who asked for help, the number of transgender people was significant.

The only way out of this dramatic situation will be vaccines, but it is unclear whether migrants without residency and health insurance will have access to vaccination.

Sex workers’-led organisations and migrants’ organisations have been united in the battle for the universal right to health and particularly for the access to Covid 19 vaccination for all, regardless of legal/residence status or health insurance.

NETHERLANDS

In the Netherlands, sex work is legalized. Even though sex workers had to stop working longer than other ‘contact professions’, most were excluded from financial support. Without income to pay rent, debt build up and some lost their homes. However, SW who continued to work independently were tracked down and punished.

Migrants SW suffered even more from the crisis. The pandemic has been used to implement repressive prostitution policies and Police violence against SW. Examples: Amsterdam warned SW via WhatsApp that the sex work ban was being actively enforced. The Police in The Hague, also via WhatsApp messages, asked SW to delete their (legal) advertisements and advised them to contact aid organizations to apply for benefits for “returning to your country of origin”.

The Police organized raids at workplaces and homes of SW by posing as clients. When sex workers agreed to meet, the place was searched up. These house raids lead to fines, evictions and in case of undocumented migrants, to deportation.

While this policy of tracking down and punishing sex workers was already a popular municipal policy, it did not have a legal basis before the pandemic. After all, prostitution is not a criminal activity, but using the ban due to Covid-19, seem to have gain a legal frame.

The majority of SW working legally in clubs and brothels were excluded from the financial support of emergency funds, although paying taxes.

Many sex workers are employed through a so-called ‘opting-in’ system which means that tax is deducted by the brothels, but they are not counted as normal employees as brothels do not pay their social security contributions.

Migrants working in non-licensed or registered forms of sex work were excluded from the state support.

NORWAY

In Norway, sex work follows a prohibitionist model. The situation was very bad and difficult for most migrant SW due to the lack of clients and no economical support from the government. Some SW were forced into exploitative relations with third parties, in order to get free housing and help for their basic needs. The immigration police chased migrant sex workers, especially female SW, accusing them of being a threat to public health, expelled or deported them.

SCOTLAND

In Scotland, sex work is regulated. Government financial support for SW was very hard to get, for nationals but mainly for migrants, who were especially suffering with no or very little help or support.

SPAIN

In Spain, sex work is regulated. Migrant sex workers are exposed to many discriminations. They could not work because of the Covid-19 measures, and could not receive the State’s economic help because of their administrative/legal situation. That is why they were and are in a very precarious and critic situation because of the debts they had to incur in order to survive.

SWITZERLAND

In Switzerland, sex work is regulated and legalized. Due to Swiss federalism, the situation is very confusing for SW. Some cantons re-opened for sex work. In those were it is still closed, sex work is forbidden and it is impossible to get a work permission. It is difficult to know which rules are valid and how the police controls the measures of protection, like to have a list with the name and phone number of each client.

SW working with the 90 days permission did not have access to the financial help of the State. SW with a permission to work in Switzerland for at least one year could ask for financial help if their earnings were less than 40% of the average turnover of the last five years (same rules for all independent workers). The situation was and is bad, mainly for migrant SW, so that many have to work illegally. Consequences: increase on STIs, HIV, pregnancies and violence. Public funds are difficult or even impossible to get for mobile/m